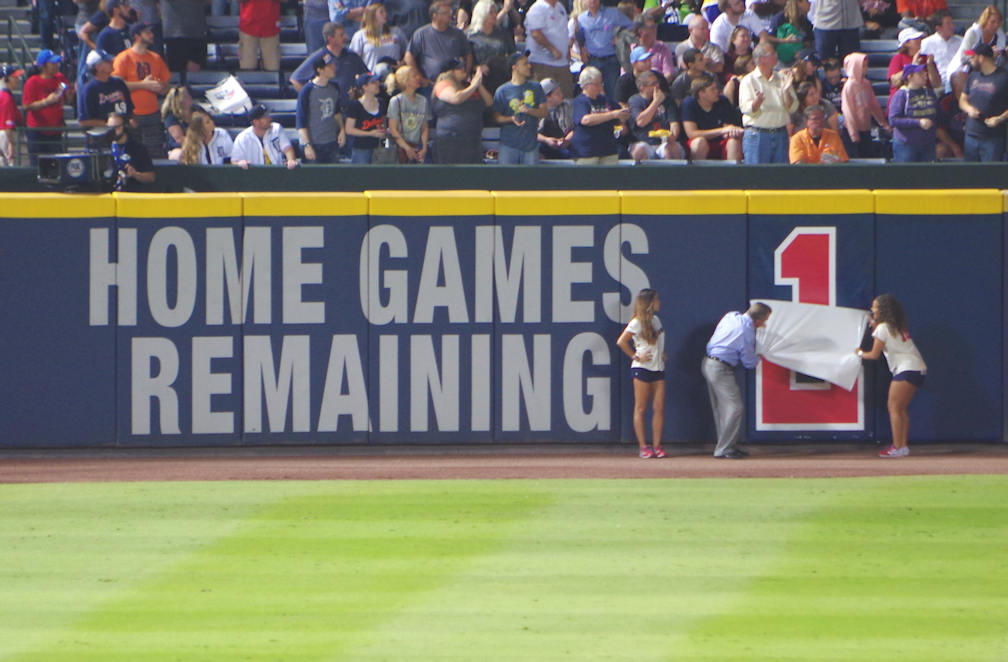

As the final baseball games at Atlanta’s Turner Field approach, we are bringing you a series of articles that provide insight into the ballpark. Here in Part 1, read the thoughts of John Schuerholz.

I conducted a phone interview with John Schuerholz for an article I wrote for USA TODAY Sports Weekly about Turner Field, as the Braves were about to move from their home park for the last 20 seasons. Schuerholz, after a 22-year stint with the Royals, nine as General Manager, came to the Braves in 1990. He served as their GM throughout the team’s remarkable streak of 14 consecutive division titles that began in 1991, and in ’97, the team moved into Turner Field. In 2007, he moved up to team president.

I asked him about the planning that went into Turner Field, which had the original purpose of hosting the 1996 Summer Olympics. We also spoke about the reasons behind the team’s decision to move out of Turner and, in 2017, into SunTrust Park in Cobb County, in the northern suburbs of Atlanta. The team is a key partner in the commercial development surrounding the new ballpark.

JOE MOCK: In your early years as GM of the Braves starting in 1990, there must have been discussions about a possible replacement for Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium (which opened in 1966). What went into the planning for Atlanta’s Olympic stadium to become a baseball park?

JOHN SCHUERHOLZ: At very high levels, (there were discussions between) political leaders and business leaders and the Olympic leaders and we the Braves, being owned then by (Ted) Turner. It was Ted’s desire that when we would have our new stadium, it would be located in the area where it’s now located. He wanted to do something to try to stimulate the growth and the improvement in this area. He was very conscious of that. But of course the Olympic Committee had to get a facility. They negotiated their deal with the State of Georgia and the City of Atlanta and ended up with this spot as the preferred spot by all of the leaders I just mentioned. So we end up where we are, which is on the southern end of the City of Atlanta. A beautiful ballpark (was) built, now in its 20th and final year for us, and it (has) served us well. Lots of great memories here, Joe. Lots of excitement created for our community, for our fans not only in the Atlanta area or the State of Georgia, but throughout the Southeast, what we refer to fondly as Braves Country. Many, many, many good and exciting times in this ballpark, some of which became historic.

JOE: And I want to ask you about some of those historic moments in a second, but first let me ask you this. In an article by Richard Justice almost two years ago, you made the interesting comment that success comes from having the right people in place. Well, does a measure of success come from having the right ballpark?

JOHN: The ballpark was a byproduct of some excellent, forward thinking and planning and creativity and imagination and desires and needs of a lot of very smart and capable people, starting with the ballpark which, of course, was the Olympic venue initially, let’s not forget. It had to serve that purpose principally, and it also had to be designed to retrofit in a way to meet our needs perfectly. And remarkably, those people with their ideas — we were at the table, we the Braves, knowing what we wanted post-Olympics and the architects and engineers and re-construction people did a phenomenal job in my opinion and I think just about all of the people in those facets of life would agree with me. I was at the Opening and the Closing Ceremonies of the (1996) Olympics. I was my patriotic self. It was a beautiful venue. People worried about the traffic and they worried about the parking and that’s all we heard about prior to the Olympics and there was not one stitch of those issues that wound their way through the fabric of what the Olympics were, what it did for Atlanta and what it did for the United States of America.

So it was built in a place where — well, you know Atlanta. Our traffic engineers probably didn’t win a lot of awards for deciding to bring two Interstate highways together through the center of this robust community.

JOE: Well put!

JOHN: So our Olympic fans from all over the United States, and all over the world actually, and people who live locally, expected traffic issues, but it was managed so well that there were no traffic problems. It was just a beautiful, glorified Olympic presentation that we all had our hand over our heart and felt like patriotic Americans, especially when Muhammad Ali put his torch to the big torch and lit the Olympic flame.

So that was done, but talking about baseball, talking about Turner Field — we knew that after the Olympics that they were going to have to build another third or fourth of our stadium. Our permanent structure didn’t exist. Two-thirds of this facility existed, but the last third — which is in center field and our offices and the 755 Club and all of the outfield seats — did not exist. They were planned, they were designed, and all of the calculations were done to make the transformation, and it was handled in spectacular fashion.

JOE: I always felt that back in the late ’90s, Turner Field was the most underrated ballpark in the Majors. It was never mentioned in the same breath as the Wrigleys and the Fenways, but I always thought it served its purpose beautifully. It was in a great spot where you could see the skyline, so it was obvious to me that smart site planners and architects did the right planning in designing the Olympic stadium so that it would result in an excellent baseball park.

JOHN: First, let me say thank you. We had a great deal of input into all of that, how this facility would look when it would become this facility after the Olympics’ use of it.

Janet Marie Smith was our baseball architect that we hired. She had done many other facilities, and Stan Kasten (president of the Braves at the time, and now president of the Dodgers) knew her to be the one to deal with this transformation, pre-design and pre-transformation, into this baseball facility. And it happened beautifully. Because of those good people, those good and brilliant and smart and capable and experienced people that put their heads together and spent considerable hours — I can remember it like it was yesterday, going over blueprints, going over diagrams, going over renderings, going over everything, and it turned out beautifully, and here we have Turner Field.

JOE: For the article that will appear in USA TODAY Sports Weekly on Turner Field, we’re going to include a Top Ten list of events that have happened there. To you, what are the top events, baseball and non-baseball?

JOHN: As I said, I think the Opening and Closing Ceremonies — which happened before it was named Turner Field, although we knew that Turner Enterprises was going to sponsor the stadium with the naming rights — but the Opening and Closing Ceremonies, which includes Muhammad Ali lighting the torch. From my perspective as a baseball executive for now 51 years and general manager of this team then, those years during our streak which began in 1991, which was before Turner Field, but once we moved into Turner Field, they continued, and that is the remarkable run of 14 consecutive division championships, which to this day, baseball executives from owners to the Commissioner’s office to general managers to Hall of Fame players are astounded that a team could win 14 consecutive division championships in any sport. That stands out to me as one of the great, proud moments of this organization, and many, many people contributed tremendously to that continual effort, in continual pursuit of excellence for such a long stretch of time.

Of course, the world championship in 1995 remains — unfortunately for us because I believe we could’ve had a few others — as the only professional world championship the City of Atlanta has ever celebrated to date.

Through my baseball lenses, those are things that stand out to me.

Of course, watching the careers of so many Hall of Fame players begin, grow, unfold and rise to the level of Hall of Fame consideration and induction, that’s a wonderful thing for me.

And the amount of attendance! Again we go back to the traffic and parking issue, Joe, and those demons that were planted in the psyche of a lot of people, we drew 3.8 million-plus people in one year in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. We drew in the three-million levels at Turner Field quite a few times. That’s a byproduct of a couple of things. One, the fans’ belief in us (that) we know how to build championship teams (so) we’re going to continue to buy tickets and support this team. We’re going to buy tickets often and come see that team. And nobody ever complained about traffic or parking, because what overwhelmed their psyche and their view of the experience was the great play of the Atlanta Braves and the fun experience they had at Turner Field. As families, as businessmen with associates, as fans from throughout Braves Country who have to drive extended distances to come visit us periodically, and they come with high expectations and leave quite joyfully.

JOE: The Braves are truly a regional team. For years, they were the only team in the Southeast. And if you were going to drive hours and hours to bring your family to a Braves game, you wanted there to be a really good ballpark to be your destination.

JOHN: I agree. The decision that Mr. Bartholomay (primary owner of the Braves from 1962 until 1976) and his partners in Milwaukee made to move that franchise to Atlanta to become the first Major League franchise south of the Mason-Dixon Line was courageous. Well, maybe the Orioles in my old hometown of Baltimore would argue that they were the first franchise in the South. When in 1954 the Browns moved from St. Louis to become the Baltimore Orioles, I remember as a child standing on Charles Street catching styrofoam baseballs from (players of) the new Major League team. Anyway, I digress (laughter).

JOE: But you mentioned watching the Hall of Fame careers of players …

JOHN: And managers!

JOE: Yes, managers, too. But you know that it doesn’t go without notice that those 14 consecutive division titles started the year after you moved from Kansas City to Atlanta to become the GM of the Braves. That prompts a lot of talk of a future induction into the Hall of Fame for you …

JOHN: Oh, thank you.

JOE: So let’s get nostalgic for a second. You’ll be turning 76 years old the weekend of the Braves’ final games at Turner Field. What emotions do you think you’ll have as the Braves are finishing up that two-decade run at the ballpark?

JOHN: Well, a bit wistful, but mostly joyful (for the) great, great, wonderful memories of the success. We worked hard as an organization, shoulder to shoulder, side by side with a lot of talented people. That was our target. We worked hard to achieve our target year after year after year after year. We went to the top of the mountain when we won the World’s Championship in 1995, but that wasn’t enough. We continued to strive and grow. Doing that stands uppermost in my mind.

From all of the correspondence that I’ve received, initially written by hand and then morphing into electronic messages, from people who were Braves fans for life and went through the trying times for most of their lives as Braves fans, and then to be able — when we won in 1991, and going back to your earlier question, I rank 1991 as the awakening. The team that finished last for three years in a row (1988 through 1990) won in 1991. We went from worst to first. It invigorated, it awakened a baseball spirit in the City of Atlanta. The caps came out. The t-shirts came out. (I received) letters from people whose elderly and aging parents in rest homes were made so happy and so thrilled and so energized, they were so happy that “their boys” — they called us “their boys” — were finally playing so well. 1991 for me as a baseball executive was as thrilling and as fulfilling as just about anything, absent the World Championship I enjoyed in Kansas City in 1985 and the one here in 1995.

JOE: You put that well. Let’s look ahead now. The Braves are about to move out of Turner Field, a facility you’ve occupied since 1997. How do you respond to critics who say there’s no way a stadium can be obsolete after just two decades?

JOHN: Well, I know they’re wrong. I know they haven’t done their research. I know they haven’t dug for the facts, so I dismiss that. We the Braves sat at the table — and by the way, we initiated these conversations — to try to acquire the land surrounding Turner Field to do here what we are now almost finished doing in Cobb County. That is to build a beautiful stadium, which we already had here, and to add to it for the benefit of the visiting out-of-town fans (and) for those who live in the community nearby, an invigorated, positive, wonderful environment of “live, work and play” right here around Turner Field. That was our goal. We sat at the negotiating table for a long time and we tried our best and we believe the City tried their best and they got to the point where they told us that there was no possibility that that was going to happen, that we weren’t going to be able to acquire that land. And so we had no choice. Our lease was expiring in three years hence and we had to look forward and find land to build a stadium so we weren’t in violation of Baseball’s rules and regulations and not be able to play the games that we were scheduled to play against our opponents.

So we found a beautiful stretch of land in Cobb County, about ten miles north as the crow flies from this site where I sit at the moment at Turner Field. So it’s not as if we moved to Timbuktu. We made it clear that we will still be the Atlanta Braves, we will have the “A” on our hat, “Atlanta” proudly across our chest. We’re representing the great City of Atlanta and the great State of Georgia. So we’re going to continue to do that and we made that assertion and we’ll live up to that. But it didn’t work, the negotiations didn’t work. I’m not going to ascribe fault to anyone. It just didn’t work. But we had to find another place to play.

But the good thing for me, if I may — I’m not a bullet-point guy. I was an old educator and taught composition and grammar for several years. Interestingly, the Georgia State University is now led by another Towson graduate Mark Becker (note: Schuerholz attended Maryland State Teachers College at Towson, as it was called until 1960. It’s now called Towson University), president of Georgia State University. Of all of the considerations we read about — we weren’t told about them, we read about what might be available to the City of Atlanta — I’m so happy that Georgia State is partner with a group that is going to be (the) new owners of this (property). It’s the best thing that could happen in my mind, so I’m happy for them.

JOE: Why do you feel that way?

JOHN: I think an educational environment presents a very healthy and hopeful cornerstone for people in a community who are looking for hope and growth and newness and pleasant environment. Not that we didn’t help bring that to people because we provided tons of jobs to the people who lived in this area and we still will even when we’re ten miles away. But I think that’s a very healthy and noble cornerstone for a project to take hold and help pull the community along with it. (Georgia State) is a growing university. Some say that in a few years, it’s going to be the most attended university in all of the State of Georgia. Right now, it’s spread out piecemeal throughout downtown, but has gained a very, very strong reputation. And so it will be helpful to the people who live in this community to have that as the cornerstone. That’s why I believe that. And I’m a little biased because I graduated from a teacher’s college and taught school and went to graduate school for degrees and all that.

JOE: How much of the decision to move was based on the needs of the fans and team to have a new facility versus being able to develop and control the commercial space around it?

JOHN: We wanted to do that here. We wanted to do that in the area surrounding Turner Field. That was our hope. That was our initial desire. That was our initial plan. That’s what we hoped to occur.

When we found out that that was impossible, we were told that it would not happen, that we had no choice. But the concept of building a Major League ballpark and a mixed-use development, we believed was valid. We believed it would work. We believed that it would create jobs, it would be beneficial to school systems where we would land based on the amount of money that they’ll get from the project, and we think all that will happen. It could’ve happened here, but it didn’t, so it will happen ten miles up the road in Cobb County.

JOE: In other cities, the decision was made to build a new ballpark in a certain spot, and then hope that development will occur around it, and sometimes it took years for it to happen, like in Houston and St. Louis. In your project in Cobb County, the commercial development is happening right off the bat, because the structures for it are being built right now, along with the ballpark. How important was it to the Braves for the commercial development to happen at the same time as the ballpark?

JOHN: We were smart enough to benefit from (and) to take advantage of the experiences of our friends and partners in St. Louis and Houston and other places where they built their new ballparks, and watched as their fans came early to the games and went into restaurants and went into bars and went into retail shops and cooled their heels waiting for the game to start.

The DeWitt family are very, very smart people and run a great organization (the Cardinals). They said, “Wait a second. Why don’t we create an environment that those people (will) want to come here, with us?” So we saw all of that happen. We watched that, so what we decided to do — and it’s never been done before. It’s the first time that a major sports arena, stadium or ballpark have been built simultaneously with an adjoining mixed-use development. And it was probably a far greater challenge than we realized at the time. At the time, we knew it was smart to do. We now realize how very challenging and difficult and demanding it is to do. We’ve got those great people — again, going back to those great people — we’ve got great people in our organization and partners in this project that have just joined together and are bringing a project out of the ground and I just can’t wait for you to see it.

I don’t use this word often, but I can’t help but use it when describing this project: astounding. To those who are in the business of developing projects, to those who are in the business of building great buildings, to those who are in the business of retail and commerce, it’s the word used most often and uttered most often when they see it even in the state of development that it’s in now: astounding.

In our next installment, you’ll read the recollections of an 89-year-old Braves fan.