By Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

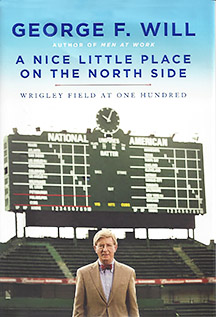

While working on an article on Wrigley Field’s long history for USA Today Sports Weekly, I told my editor that George Will had just released a book on The Friendly Confines. The editor told me to go get an interview with the Pulitzer Prize winner.

It took some doing, but thanks to the publicist at his publisher, I was able to book time with Mr. Will. He was kind enough to speak to me as he was changing planes at DFW Airport. What a gentleman he is!

We talked about A Nice Little Place on the North Side, his book which had just been released. Unlike many interviewers who speak with him, though, I had actually read every word of it — and I loved every word of it.

I could only use a few quotes from him in the Sports Weekly article, but he had so many interesting things to say that it just didn’t seem right to keep his insights under wraps.

So here is an only-slightly-abridged version of the conversation I had with the nationally known columnist, TV commentator and author … and pre-eminent baseball fan.

|

| Cover image used by permission of Crown Archetype |

JOE: The release of your book was timed to coincide with Wrigley’s 100th birthday. The birthday wasn’t the only reason you wrote it, though, was it?

WILL: I’m interested in the chemistry of loyalty generally, and I’m interested in urban life and I’m interested in Chicago, which has always been a fixation for this downstate Illinois boy. It represented cosmopolitanism, and frankly it hasn’t let me down. It’s still, I think, my favorite city in the whole world.

JOE: What observations had you made about Cubs fans that led you to write the book?

WILL: Well, I think observing one Cub fan in particular — me — it’s the extent to which native stubbornness enters into this, as well as the nagging fear that if I ever changed loyalty, they’d start winning. And also the sense that when we get attached to a team … I remember talking to Andy MacPhail, who was president of the team … in ’94 when we were heading into the strike and (there was) all of the talk about replacement players. Baseball worried a lot then about whether fans would come out to see replacement players, Are they just so attached to the radio broadcaster, the ballpark, the logo, the team uniforms and all that? I don’t think they’re that attached to them, but they are awfully attached to them.

It’s a very complicated business, this tribe we join. It’s a completely voluntary tribe. It only exists when games are being played, sort of. But it assembles at about one o’clock or seven o’clock in the evening and it lasts about three hours. But the beauty of baseball, as Earl Weaver once said, this ain’t football. We do this every day. And we do it again tomorrow.

JOE: I think 162 games is a pretty good test of which teams are better than other teams. It’s not like football where you might play a team once a season.

WILL: I think that’s right. I think baseball is the severest meritocracy. And of all the numbers, and God knows baseball loves its numbers, the hardest for the fan to fathom is 162. That’s how hard it is.

JOE: You devote more pages in your book to Ernie Banks than any other Cub. Why?

WILL: My formative years were the 1950s when he was the Cub athlete. That’s a little bit unfair, but not much … There was only one star. And in the midst of this otherwise dreary decade, he was hitting all those home runs, more I think than anyone else in the second half of that decade. He wins the MVP award twice.

JOE: That is something to root for.

WILL: Yeah. Something? It was the thing (to root for). Definite article: the. There was nothing else going on there. And his relentless cheerfulness was an example to us all, and a reproach to some of us.

JOE: Do you think Cubs fans treat their heroes differently than the fans of other teams treat their heroes?

WILL: I think Cub fans probably have fewer genuine heroes to root for.

JOE: Right. If you’re a Yankees fan, you’ve always had lots of heroes to choose from.

WILL: Yeah, it’s like rooting for Microsoft with the Yankees. I mean, what’s the fun? If they don’t win the World Series, then it’s a deflating year.

I do think Cub fans tend to cut their heroes a lot more slack.

JOE: Why do you think that is?

WILL: Lord knows they know how hard the game of baseball is, because they’ve seen other people do it better.

JOE: Usually playing for the visiting teams.

WILL: Yes. They used to say the best thing about being a Cub fan is that when you go to Wrigley Field, you always got to see the bottom of the 9th.

JOE: I know you touch on this throughout your book, but why do you think that Cub fans continue to flock to Wrigley despite the team’s disappointing results?

WILL: Well first, it’s a great experience. It’s a great experience in the ballpark and around the ballpark. One of the charms of Wrigley Field is that, like Crosley Field in the past and Forbes Field and Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis and Shibe Park in Philadelphia and particularly Ebbets Field, it is embedded in an organic, living neighborhood. And it’s not so big that it overshadows the three-story buildings around it. So the neighborhood is fun and the ballpark is fun. And it may have something to do with the fact that people come by public transportation because there’s simply no parking. You get on the El up on the North Side or on the South Side or you get on a bus and you look around and there are other people with their Cub gear on. It’s this tribe slowly assembling before the game … and as I say in the book, being a Cub fan is a lifelong tutorial in deferred expectations and deferred gratification (with) the emphasis on deferred, not giving up on (the gratification).

|

| Image of the back cover of A Nice Little Place on the North Side used by permission of Crown Archetype |

JOE: So there’s a certain optimism to being a Cub fan, because if you don’t have that, what is there to look forward to?

WILL: Exactly. I mean, the numbers in baseball are pretty telling. Every team in baseball … when the season starts really knows it’s going to lose 60 games and it’s going to win 60 games. You play the whole season to sort out the middle 42. Some teams are just better at that than others. What strikes a Cub fan is that you’d think over 145 years, just randomness would produce a (World Series) victory.

JOE: As you point out in the book, it’s a statistical aberration for a team to lose so many more than they win, as the Cubs have done.

WILL: Yes, which is why there is a sense in which my little book is a business book. It’s about a business model that didn’t work. (It was) the temptation that P.K. Wrigley (team owner for decades starting in 1932) succumbed to — and he was an engaging, winning sort of figure in a losing context — a very sympathetic man, I think, who didn’t really want the role that life cast him in. He made the not-indefensible decision (that) our team isn’t very good. Our park is spectacular. Let’s merchandise the latter. And the ivy will be lush and the grass so green and the sunshine so warm and the beer so cold that people will not dwell on the scoreboard.

JOE: And you wrote about research done by Moskowitz and Worthem that would seem to support a hypothesis you have, that the ballpark is a big reason behind the Cubs’ futility.

WILL: Well, again, if Cubs fans were less loyal, if Cub fans were more fastidious about baseball, if Cub fans didn’t come out for the experience, they might’ve been more demanding and attendance might’ve varied more directly and dramatically with the success on the field, which would’ve produced a much more powerful incentive to improve what was going on on the field.

On the other hand, that’s part of the mystery of what I refer to as the chemistry of loyalty. I’m not one who likes the phrase “lovable losers,” because there’s nothing lovable about putting a mediocre-at-best product in front of customers more often than not for a century.

The sustained experience of adjusting to disappointment does, as some of the people I quoted (in the book) suggest, rework the circuitry of the brain after a while.

JOE: What does science teach us about Cubs fans?

WILL: The whole idea of “this is your brain on Cubs” (in A Nice Little Place, Will refers to what he calls a “naughty book” entitled Your Brain On Cubs: Inside the Heads of Players and Fans. Says Will, “It is a collection of essays by doctors and others knowledgeable about neuroscience and brain disorders associated with giving one’s allegiance to a team that last won a World Series exactly one hundred years before the book was published.”) was probably a stretch, but an amusing stretch, and one with just enough plausibility to make it a hypothesis worth looking at. If someone said (about that part of the book), “That’s all crazy,” I wouldn’t be shattered.

JOE: But that’s what makes an interesting book, because you’ve held up this issue of Cub fan loyalty and looked at it from a variety of perspectives.

WILL: And I’m not really sure that being a Yankee fan is good for the soul, because you get an entirely wrong view of life. Again, the beauty of baseball is that there is a lot of losing in it, even when you’re very good. I mean, if the Chicago Bears start 0-3, the Bear fans will go to bed and not take solid food. I mean, they will just be distraught. For any baseball fan, 0-3 is just a stumble out of the gate, that’s all. Again, this is part of the experience of baseball. Football is a spectacle. Baseball is a habit. It is a habit nourished by going to the ballpark … This is the difference between NFL fans and baseball fans: if your enjoyment of the experience depends on the outcome, don’t go. Even the best team in baseball is going to walk off the field beaten 60 times (a season). That’s why, for a baseball fan, the enjoyment does not depend on the final score. In that sense, the baseball fans were right.

JOE: Tell me about the impact that beer has on the attendance at Wrigley Field.

WILL: Yeah, it’s what economists call price elasticity. Cub fans will put up with (ticket) price increases, but they draw the line at increased beer (prices). Now, they may be proving a little too much with statistical correlations, but it’s great fun anyway! To make the price of beer the great variable (in relationship to home attendance) was great fun.

JOE: Even though Wrigley has had lights for a couple of decades now, the Cubs still play more day games than any other team. Does that have an effect on the players?

WILL: Well, it certainly did for a long time. … One of the recent (Cub) managers once told me that the Cubs had five different starting times (for home games). That’s too many. As you know being around baseball, ball players are relentlessly metronomic in their patterns, so that was difficult (on them). Also, for a while, some people thought having too many day games left the players far too much spare time in the evening, to be down on Rush Street back when Rush Street was a big deal — but to go out and get into trouble.

|

| George Will throwing the ceremonial first pitch at Wrigley Field, April 6, 2014. Image is from MLB.com. The entire pitch sequence can be seen here |

JOE: In your opinion, what are the biggest baseball-related events in Wrigley’s 100-year history, and why?

WILL: Well, the two most famous games are the Bartman game and the Babe Ruth game, and the second one didn’t happen and the first one shouldn’t have happened. You know, one of the great ironies is that the Cubs had their greatest apogee as a team before they moved into Wrigley Field. The joke going around a few years ago was “What do the Cubs and the Marlins have in common? Neither has won a World Series in their new ballpark.”

JOE: You were in attendance at the fateful game on October 14, 2003 (the “Bartman game”). What do we learn about Cubs fans from that night and from its aftermath?

WILL: That’s a good question. First of all, I have to wonder whether the slice of Cubs fans who were there for that game was representative of Cubs fans generally, because you get a different cohort in the postseason. Moises Alou to this day says that he’s very sorry he made that gesture of frustration and anger. If he hadn’t done that, I’m absolutely convinced the game would’ve gone right on, and nothing would’ve happened and Bartman would be living a happy life, going to Wrigley Field a lot.

I was sitting with (Cubs President) Andy MacPhail upstairs and all Andy did was, when the umpire made the call (that there was no fan interference), he leaned over and looked at the replay on the monitor and said “good call” and sat back, which means of course that Bartman did nothing wrong. He didn’t reach out into the field of play. Never mind the fact that Bartman was surrounded by people trying to do the same thing.

As I said in the book, sitting up there in the stands, I didn’t hear that stuff. We couldn’t tell what the fans were chanting, “Ass hole, ass hole,” and all that, which was really quite ugly. And I didn’t realize this until I saw the ESPN 30 For 30 movie about it.

JOE: Should this game be remembered as one of the biggest events in Wrigley history?

WILL: I think it has to be, because the Cubs were just five outs from their first World Series since 1945. And because it showed that — the baseball crowd, “take me out with the crowd,” is part of the fun of the game, but that night the crowd, or a substantial portion of the crowd, was not something to celebrate. And we have to look at that in the face. It’s certainly a black eye (on Cubs fans), but we can’t tar everyone in the ballpark that night with that behavior, but neither can we ignore the fact that the significant portion of the people there behaved badly and cruelly. It was just cruel and (was) bullying. It was just unpleasant.

JOE: To this day, Bartman won’t appear on camera to talk about it.

WILL: Which speaks well of Bartman, because he could’ve cashed in on this. I look forward to the day when the Cubs invite Bartman to come out and throw out the first pitch.

JOE: And I hope everyone stands and applauds him.

WILL: I do, too, and they would, too. There’s no question. My God, if they gave Ryan Braun a standing ovation yesterday 90 miles north (at Opening Day in Milwaukee), he can get an ovation, too.

He added this about A Nice Little Place on the North Side:

WILL: If you’ve read my first baseball book, Men At Work, then you know that I’m relentlessly anti-sentimental (from the) anti-romantic school of baseball writing. The Wrigley Field book is I think my 14th book, and usually getting the title is the hardest part. With Men At Work, I had the title before I had anything else, because I wanted to write a book that said “these are not the Boys of Summer. These are not boys, they are grown men, and what they are doing is work and it’s really hard and it’s dangerous.” I brought that sensibility to looking at the Cubs and Wrigley Field. Not hostile and not cynical. Uninvolved.

If you have any thoughts about the interview above, please post them here … but no shots about Mr. Will’s political commentary. I’ll remove the comments section if people turn it into a referendum on his political views:

Beautiful interview with one of the most informative writers out there. I haven’t read the book yet but Mr. Will’s insights on the game politics and what not are a great read.