Back to page 1

The Essentials

So what is it like to attend a game at Nationals Park? Is the game-day experience everything that it could be?

First, your options for traveling to the park are, in a way, limited because taking your car might not be a good idea due to the lack of parking. The roads to handle the traffic are there, but the parking spaces aren’t. Washington’s excellent, clean Metrorail system is a good choice, and at least for the first season, the Nationals are operating a free bus service for fans who park their cars at RFK Stadium.

The tickets, though, are anything but free. The exact prices, as is becoming the trend these days, depend on whether the seat is purchased for the season, partial season or a single game … and if that contest is a “premium” game. Now, I know any new park is going to maximize revenue to the team, but that team needs to remember that the local taxpayers coughed up over $600 million to construct their money-printing machine. It’s no surprise that the “Presidential” seats behind home plate are $325 and the “Diamond” seats right behind them are $170 ($335 and $175, respectively, for premium games). What’s troubling is that the seats in the outfield are $35 ($39 for premium games), and $27 ($29) right under the scoreboard.

Not until you examine the Terrace Level, which is the uppermost deck down the first-base line, and the Upper Gallery Level do you find seats that are $18 ($20) and $10 (also $10 for premium games). I will give the team credit for offering up two sections — that are not very large — where the seats are $5, but they can only be purchased the day of the game. My point is that there aren’t nearly enough affordable seats in the park, especially for the average citizen of the municipality that paid for the facility.

|

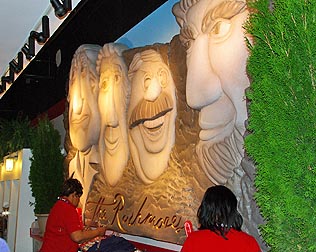

Once you’re inside the gates — most likely on the north side, since that’s where the majority of fans are entering the park — you’ll probably encounter a president or two. The Nationals get a lot of mileage out of the cartoonish “Rushmore” mascots, featuring the same four presidents that actually appear on Mount Rushmore: George Washington; Thomas Jefferson; Abe Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt (above left). Not only do they mingle with the fans before and during the games, they also appear on the wall behind the cash registers in the main souvenir shop and, most importantly, they engage in a Milwaukee-sausage-style race between innings during the contest.

That souvenir store (above right), by the way, is large enough to accommodate the crowds on any day other than opening day. The prices on the merchandise are not bargains — where the average adult T-shirt is $25 — but neither are they out of line with the stores at other Major League parks. Souvenir sales, especially during the first season back in Washington, were a big problem during the Nationals’ RFK days, due to the lack of space for adequate stores.

|

On the food front, the ballpark does a nice job of mixing local fare with the usual baseball foods. The two stands that seemed to generate the most buzz during the park’s first days were Ben’s Chili Bowl (above left), an absolute institution in D.C., and Noah’s Pretzels, which features their specialty in the shape of the Nationals’ curly “W” logo (above right). The longest concession lines I saw at the park, by the way, were at Ben’s.

|

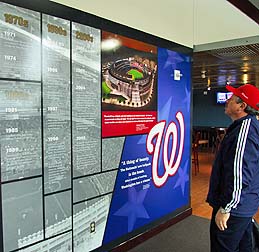

The “jog” in the outfield fence is a fairly subtle way that Washington’s baseball past is remembered. There are several other ways in which that history is embraced at Nationals Park. The first, as mentioned earlier, is along the walkway leading to the home-plate entryway. There are markers that describe major baseball moments in Washington’s past (see above left). These are very well done. On the right above are large, detailed timelines that adorn the concourse behind home plate. Again, I can’t say enough about how important it is to remember the sport’s past.

While the kids might not care that much about baseball’s history, they will still be delighted with the attractions for the younger set. Most of the activities for kids are located in the right-field corner, as there’s a red-white-and-blue playground (below left), and arcade-style games can be found nearby on the ground level of the right field parking-garage building. There’s even a Build-A-Bear store (below right) where youngsters can assemble their own “Screech,” which is the Nationals’ eagle mascot.

|

As you walk around the ballpark, you’ll notice that the architects put a lot of effort into designing great vantage points where fans can look down on the action from places other than their seats. I’ve always thought that Safeco Field in Seattle leads the Majors in the most — and best — vantage points from which to watch the action. Well, Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia and Nationals Park aren’t far behind. The spot shown in the photo below on the left is one of many such locations where you take in the view from the concourse.

And speaking of views, when the site for the stadium was selected in 2005, there was a lot of hype about how great the views would be from within the park, especially because the Capitol would be so visible. Well, that didn’t work out as well as they’d hoped, as an office building popped up between the park and the Capitol, blocking the view from thousands of seats. The center photo below, which was taken from the press box, shows one vantage point from which the Capitol can be seen, but the building just to the right of it in the picture is the one that blocks the view for many.

|

Although you can’t see it from any of the seats, the Anacostia River provides additional views. Part of the upper concourse lets you see the river, and in the shot on the right above, some fans take a break from watching the game to enjoy a twilight view of the Anacostia and the Frederick Douglass Bridge.

|

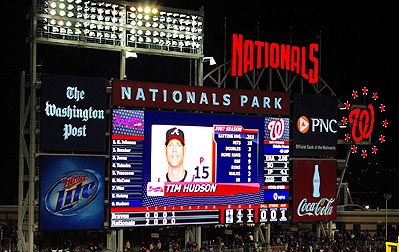

Finally, one of the park’s nicest features is its stunning scoreboard. The board is essentially one huge video screen — a very high resolution screen, at that. Its color and clarity are amazing, as is its size. In fact, only the brand-new screen at Kauffman Stadium in Kansas City is larger.

Summary

And now for my rant about the D.C. government. Time and time again, Major League Baseball had wanted to bring a team back to the Nation’s Capital, but the District of Columbia failed to get its act together. Even after an iron-clad agreement had been struck in the fall of 2004 to build a new ballpark, thereby ushering in a new era because that meant that the Expos franchise would come to D.C., members of the city council would cause the deal to unravel. This forced MLB, which was owning and operating the team at the time, to declare that they weren’t coming to Washington after all.

How, indeed, did we ever reach the historic moment shown below, when Odalis Perez delivered the first pitch at Nationals Park on March 30, 2008?

|

As you know, the deal was resurrected and the team ended up transferring to Washington to play at aging RFK Stadium for three years while the new park was designed and constructed. One of the interesting ironies of the political games that were played regarding the stadium is that an ardent opponent of the deal was councilman Adrian Fenty, who tried and tried to knock the deal off-course. Mr. Fenty is now Washington’s mayor, and who do you think was there to yell “Play ball” into the public-address microphone on opening night of the new park, as if he’d been a supporter of the park all along?

Such are the ironies and hypocrisies of the local government in our Nation’s Capital, and those of us who live “outside the beltway” can barely comprehend them. Why is all of this important in a review of the new ballpark? There are two reasons: first, the very fact that the stadium now exists is remarkable, because it occurred despite the bureaucratic bickering and back-room wrangling within the dysfunctional government; and second, the government’s constantly evolving requirements and ever-changing liaisons forced the designers of the park to deal with challenges that architects should never have to endure, resulting in compromises and accommodations that manifest themselves in the finished product.

Put another way, it seems to me that the architects of Nationals Park were faced with numerous obstacles that made designing a ballpark — especially one as important as this one because it’s in the capital city of our country — ridiculously challenging. The fact that the ballpark turned out so well is a testament to those designers, because this occurred in spite of the challenges erected by the city.

One obvious example of these challenges is that HOK, designer of the majority of the current MLB, spring-training and Triple-A parks in the country, found it necessary to partner with a local architecture firm to get the business … then HOK had to agree to have two of its principals actually work out of an office in Washington throughout the design and construction process. This is ridiculous. If the Mets and Yankees can trust HOK to do the appropriate design work from their sports-facilities headquarters in Kansas City, why can’t the District of Columbia?

When you boil it all down, the objective of the architecture team was to design the ballpark and make sure it was finished on time at a cost of no more than the agreed-to amount of $611 million. They delivered that. The city, meanwhile, insisted on overseeing the development surrounding the stadium site (the site selected for the park was badly in need of “urban renewal”), intending for nice projects to be in place by Opening Day 2008. That clearly did not occur, and as mentioned earlier, that was the District’s responsibility.

So Nationals Park — which no doubt will go through a name change when an appropriate corporate sponsor can be found to purchase the naming rights — turned out well, despite the unprecedented challenges of working with the District of Columbia. I’m sure HOK appreciated getting the nod to do the design work regardless, and indeed they did some of their finest work ever here, especially inside the park. Still, though, one can’t help but wonder what kind of masterpiece they might’ve designed if they’d had the creative free reign to design, say, another PNC Park. Truly, they might’ve created a national monument for the ages.

As it is, it is still very special, and its “green” elements lap the field in this emerging area of importance.